Intro

Well, I am glad you made it here! You must be wondering:

- What is this blog post precisely about?

- Why couldn’t I stop walking?

- And you might be wondering, what is Facebook’s logo doing among these other tech tools?

Let me answer your questions and more!

This blog post is mainly about the work I did, the technical challenges I faced, and the future directions of the only project so far that often had me walking around my room thinking about how I’d design a solution to a specific problem. This is the project I worked on during my second consecutive Google Summer of Code, in 2025, with a new organization: openSUSE. It spanned about three months, from July to October.

Project Goal & Background

Implementing AI-Driven Pull Request Test Selection in Uyuni from the ground up. Uyuni is a large open-source project under openSUSE, and is the open-source upstream of SUSE Multi-Linux Manager, a configuration and infrastructure management solution for administering multiple Linux systems.

To ensure code quality, Uyuni uses Pull Request Acceptance Tests. These tests are run on new pull requests to prevent breakages from reaching the master branch. They provide fast feedback to developers, helping them fix issues while they are still focused on their tasks. Currently, Pull Request Acceptance Tests execute most of the test suite, with an average runtime of an hour. This delays feedback for developers and increases infrastructure costs.

AI-Driven Pull Request Test Selection, technically known as Predictive Test Selection (PTS), is a machine learning approach that uses past pull requests, test results, and other relevant information to predict which small subset of tests is most likely to fail for a new pull request. Running only this smaller subset of tests speeds up developer feedback, reduces infrastructure costs, and maintains high test coverage. Inspired by Facebook engineers’ research paper on PTS, the goal of this project is to implement this technique inside Uyuni.

The reason we (and other companies that created PTS as a commercial product) have faith in PTS is because the paper presented impressive results by training a model on machine learning features like:

- Extensions of the modified files in the PR (e.g., java, css, ts)

- Number of modifications that happened on the modified files over several recent days, which highlights active areas of development that are more prone to breakages

- Test category

- Number of steps inside the test

- Historical failure rates of the test over several recent days

They were able to consistently detect 99.9% of PRs that introduce a test failure while selecting only 33% of the total test suite.

If you are interested in reading more, this is the article summarizing their paper.

This project is about building PTS from scratch, initially without even storing pull request test results.

Why I Chose This Project?

The answer is simple. I thought it was very cool, and the Facebook engineers wrote a great paper. I was building the project from scratch, so it was a greenfield where I had to design solutions every step of the way. I was learning new concepts in testing, and I am generally interested in machine learning, and I had previous experience in GSoC 2024 working with automation and continuous integration using GitHub Actions.

I must thank my mentor, Oscar Barrios, for proposing this project and writing an excellent description. Had it not been so well written, I wouldn’t have been hooked.

What Was Done & Challenges

If you’re only interested in what was done, feel free to read just what’s in bold.

If you’d like to understand the thought process, the challenges I faced along the way, get insights into new concepts, and learn from the solutions to these challenges, then I’d recommend reading everything.

And if you want to dive deeper into the technical details,

the predictive-test-selection directory

in Uyuni contains all the code along with a very detailed README that explains everything in depth.

You can also check out our GitHub project board,

which we’ve been using to track the progress of the work.

The project consists of three parts, each logically separated according to its related content and the amount of work involved.

1. Gathering Training Data

This was the biggest part of the project. It took two-thirds of the work done this summer, which is around two months of work.

The first step is to design how I will gather the training data, consisting of data related to the PRs and data related to the tests, so that I can train a machine learning classifier on a large number of (pull request, test) pairs so that, when given a PR and a test, it can predict the probability of this test failing on this PR. The machine learning features I focused on gathering are precisely the ones listed in the previous “Project Goal & Background” section.

For context, Uyuni uses Cucumber for writing their automated tests, and as I mentioned, we didn’t have a system for storing the pull request test results, let alone the metadata for each test in the suite, such as its category, number of steps, and historical failure rates. The historical failure rates were tricky, since we wanted to be able to get how many times a test failed for any time range.

An important note in case you decide to dive into the technical details, you will find the word ‘Feature’ used a lot, this is because a test in Cucumber is called a ‘Feature’, so ’test’ and ‘Feature’ in the Cucumber context are interchangeable.

- When the Cucumber tests run, they generate Cucumber JSON reports. We knew that if we processed these reports

we would be able to obtain the test results along with the other metadata we want, so these reports were what we wanted to store

and link them to their corresponding PR GitHub Actions test run. My first intuition was to upload the Cucumber reports as GitHub Action artifacts,

I did that in this PR in April, two months before I started working on the project so that we could gather as

many test results as we could, but there was a sneaky trick with GitHub Actions syntax that we discovered later on when I started working in June, which prevented

the reports from being gathered correctly, so as soon as I started, I found and fixed the issue in this PR and we were then

reliably storing all the Cucumber test reports for each GitHub Action test run as GitHub Artifacts.

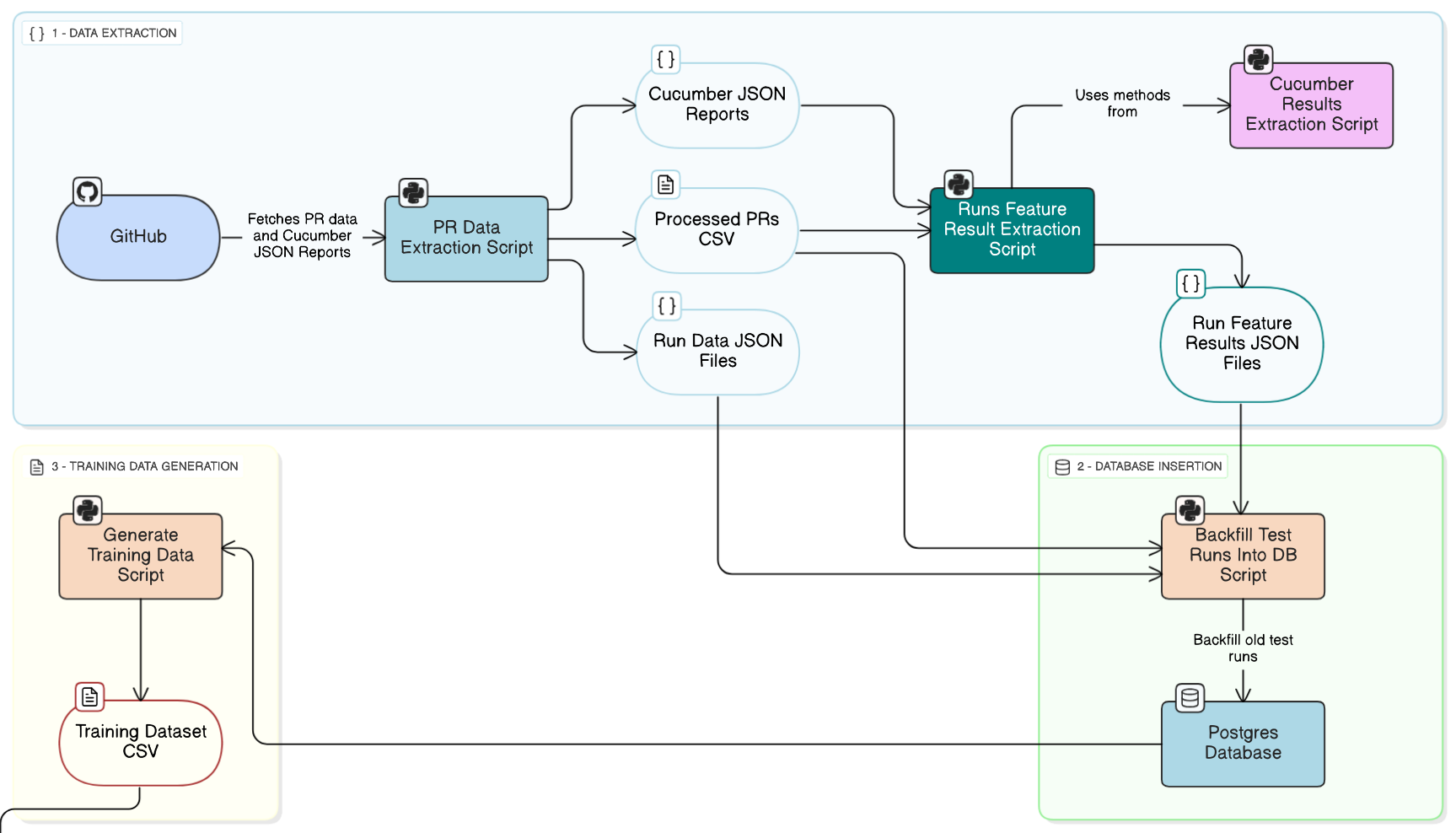

Generally, this summer I learned a lot more about working with GitHub Actions in production since we faced a lot of GitHub Actiony tricks throughout the project. - Created a script that extracts the PR features (modified files, their extensions, and modification history) and downloads the Cucumber reports stored as GitHub Artifacts for all test runs across all pull requests created since a specified date. PR

This script had a lot of playing around with Git and GitHub API limitations to accurately identify the test runs associated with each PR, as multiple test runs usually happen on a single PR as they are triggered whenever a developer pushes new commits. - Created a Python module for accurately extracting test results, test metadata, and logging test statistics from the Cucumber JSON reports.

I did my best to try to not reinvent the wheel and to search for a Python library that already does this standard thing, but I surprisingly couldn’t find one, so I created it from scratch. PR

This was tricky since the Cucumber JSON report structure is that you have a top-level array containing all the tests that ran, but you don’t have a key that directly tells you whether each test passed or failed. Instead, inside each test there are sub-tests, and inside each sub-test there are the atomic steps that get executed. Only these atomic steps have a key that says whether they passed or not, so to determine if a test passed, you need to check all the sub-tests and all the steps inside them. There are other tricks like having steps that get skipped, and multiple others that made this part fun and challenging. I was able to verify that my module works correctly by outputting identical test statistics and comparing them to the ones Cucumber outputs when it executes the tests. - Designed and deployed a PostgreSQL database on a SUSE AWS server that enabled storing all Uyuni PR test runs

along with their corresponding test results, modified files, and test metadata. Designed

with the ability to directly query historical test failure rates.

The reason we decided to store the results in a database and not rely on GitHub Artifacts is that GitHub Artifacts expire after 3 months, and we wanted to preserve test results for a longer period. Additionally, I was thinking that we would need something like a time-series database to be able to track the test failures, but this relational database design allowed us to store test results and compute historical test failure rates using a single system.

You can find more details about the database design, why we didn’t store the JSON reports on an external server, and why I specifically chose Postgres, in the beginning of the predictive test selection README. - Created a full pipeline for backfilling previous PR test runs and results into the Postgres database using the SQLAlchemy Python ORM. PR

- Designed and implemented a GitHub Actions job for automatically inserting new PR test runs into the database,

but it wasn’t merged because, when tested in production, we couldn’t pass the database connection string (stored as a GitHub secret)

to the GitHub Action due to Uyuni’s fork-based contribution model and the current implementation of the Uyuni test suite workflow.

The exact issue is stated in the first comment in the PR.

Currently, we don’t have an automatic process to insert new test runs into the database. This can only be done manually using the backfilling pipeline. As a result, we decided to postpone working on this since it isn’t a blocker and move on to model training. - Created a script that generates the full training dataset as a CSV file from the Postgres database.

An example of the dataset can be found here.

A challenging and interesting part that I faced in this script, one that generally appears in machine learning projects, was data leakage. An example that was occurring here: if a PR was created one month ago, I had to make sure that features such as the modification history of the files in the PR or the tests’ historical failure rates used only data from before the PR was created. It must have no idea about modifications or failures that occurred after it was created. This ensures the training data correctly mimics the production data.

This is the diagram that shows everything done in this part.

After finishing this part, I gave a 15-minute progress update presentation in the Uyuni community hours. You can check it out here. If you are interested in the training data structure and the database design, you will find this talk very useful :)

1.5. Selenium Conference

My mentor, Oscar, suggested that I apply as a speaker in the Selenium Conference to showcase the work I did in this project in the upcoming conference which will take place in Valencia, Spain in May 2026. I obviously thought it was a very cool idea and that we would have a lot to show, so I spent almost two weeks getting familiar with the conference, writing a very well-polished proposal, understanding the Spanish visa process in Egypt, and applying to the conference.

I am very proud of the proposal I wrote, and I believe we have a very good chance of being accepted. I will be notified if I am accepted or not on November 14th, and I will continuously edit this blog with any new updates. You can check the description of the session I submitted and wish me luck!

2. Model Training & Calibration

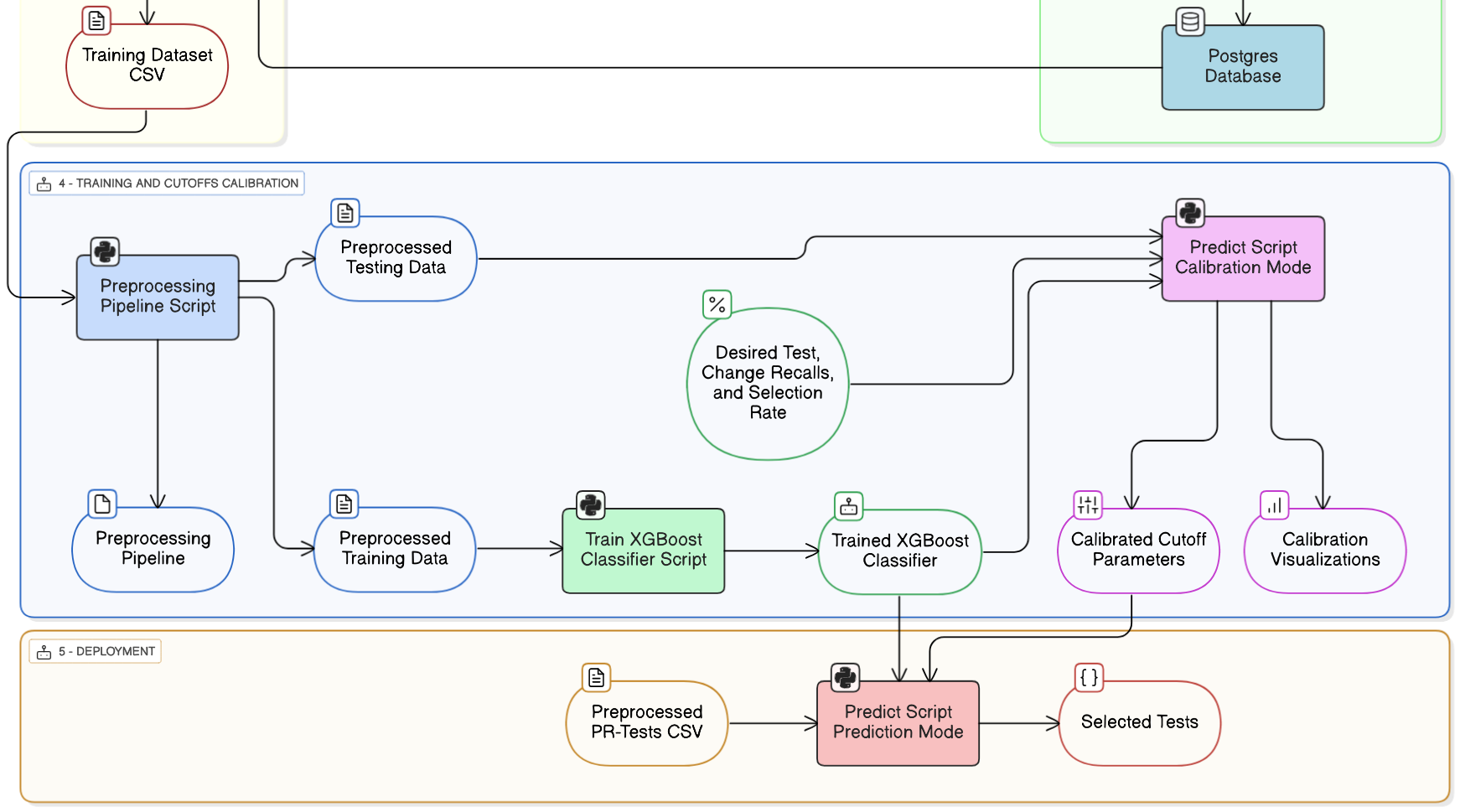

- Implemented a preprocessing pipeline that takes the gathered training data, performs data quality checks

and cleaning, applies a time-ordered train/test split, preprocesses the data,

and saves the preprocessing pipeline for production use. PR

This was one of the parts that had me frequently walking around my room, thinking about how to approach it.

The idea of preprocessing is to convert data into a very specific structure where everything becomes numbers that a machine learning model can train on. The challenge was deciding how to preprocess features like file extensions, test names, and test categories, and, more importantly, how to handle cases in production when a PR includes something the model has never seen before: a new file extension, a new test, or even a new test category.

On top of that, I had to make sure the exact preprocessing pipeline used during training was saved and could be used identically in production. This made the task both challenging and exciting. During one of my late-night research sessions, and many walks around my room, I got curious whether others had implemented predictive test selection in practice. I found a few commercial offerings and thought, why not reach out to one of the lead engineers who built one of them? So I contacted him on LinkedIn, introduced myself and the project, and asked if he’d be open to a quick call. To my surprise, he was excited to talk! We had a great call where I asked about how they handled the same problems I was facing, along with several deployment-related questions that had been on my mind.

This summer, I’ve come to realize that reaching out to people is one of the most valuable habits a software engineer can develop. I know many great engineers who never think to do it or assume others won’t reply, but this summer, my habit of reaching out has been incredibly rewarding. It’s led me to connect with and learn from some truly awesome people. - Created a script that trains an XGBoost classifier on the preprocessed training data,

performing hyperparameter tuning with time-based cross-validation,

while handling the severe class imbalance (tests that fail are far fewer than tests that pass)

- Created a prediction program that calibrates the optimal cutoff parameters that control how many tests are selected, by defining a probability cutoff (e.g., only select tests with a failure probability higher than 60%) and a count cutoff (e.g., always select at least the top 10 tests with the highest failure probability) These cutoffs are what will be used in production to select the subset of tests to run on a PR, and are what control the trade-off between the number of tests to be executed and the reliability of predictive test selection. These cutoffs are calibrated based on three desired performance metrics that are given to the program as input. PR

- Minimum percentage of PRs with failures we want to correctly identify in production. (most important)

- Minimum percentage of failed tests we want to correctly identify in production.

- Percentage of tests we want to be selected on average.

- Additionally, the prediction program, given a PR, is able to use the trained classifier along with the calibrated cutoffs to output a list of the selected tests ranked by failure probabilities.

Based on the training and test data that we currently have, our model was able to correctly identify 100% of PRs with failures (always predict at least one failing test), identify 94% of tests that fail in general, while selecting on average 45% of the total tests in our test suite.

This is the diagram that shows everything done in this part

3. Deployment

We planned to first deploy it as a test, keep the old test suite running all the tests, and monitor prediction performance to ensure it meets our desired metrics before fully deploying it and only running the tests it predicts. I wrote a detailed plan for implementing this PR but didn’t have the time to implement it after university and my graduation project started.

Deployment will have a lot of interesting challenges, some of which we are currently aware of:

- Monitoring production performance.

- Retraining the model periodically on new PRs so it stays up to date.

- When we fully deploy the model and run the subset of tests it predicts, this will pose a challenge with retraining since now we don’t have all tests running on each PR to train on them, we only have the subset of selected tests running on each one. Then we can’t know if we missed a failing test since we didn’t run all the tests. The Facebook engineers proposed an interesting way to handle this, which will be interesting to implement. I like to think of this problem as the Ouroboros symbol where if we don’t create a solution for it, our model is eating/damaging itself. When I discussed with the lead engineer who implemented predictive test selection commercially, he actually told me they hadn’t fixed this and still were getting great results, which is interesting, but I am sure tackling this problem will be very cool.

- Detecting new tests that the model wasn’t trained on and always running them without predicting their probability, then ensuring in the next cycle of retraining that this new test ends up in the training set.

- Handling tests being deleted from the test suite.

I’m excited to continue this work and will update this blog with any new progress.

Next Steps

- Implement automatic insertion of test runs into the database.

- Partial deployment to automatically predict which tests to run on each new PR, without executing them.

- Monitoring production performance during partial deployment.

- If results aren’t satisfactory, consider subtle improvements across the pipeline to improve performance (e.g., check other ways to handle class imbalance, experiment with more PR-related ML features, don’t train on PRs that contain edits to Cucumber test files, etc.)

- When we reach satisfactory results, implement full deployment.

- Polish my Cucumber test results extraction module and publish it as a Python library for extracting all possible info from the Cucumber JSON reports, can call it ‘cucumber’ or ‘pycucumber’ :)

I really enjoyed reflecting on the work I did throughout this summer. I hope you enjoyed reading it too!